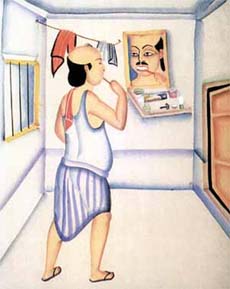

(Kalam Patua with his works - file photo. Source Net- all pics)

Far away from Delhi’s busy streets, towards the end of South

Delhi, at Anandgram where the Sanskriti Foundation is located a small ‘retrospective’

is on. The word retrospective brings an elaborate display, a huge catalogue and

somewhat crowded gallery spaces into our minds. But in the multipurpose gallery

of the Sanskriti Foundation, West Bengal based Kalam Patua’s retrospective does

not evoke such grandeur but each work displayed there proves that it is not the

visual grandeur nor is the lighting techniques that make a work of art worth

focusing on. The simplicity of Kalam Patua’s carefully learnt and traditionally

earned Kalighat and Patua styles of painting respectively enchant the viewer.

Curated by Jyotindra Jain, the master art historian of Indian folk and traditional

arts, this retrospective of Kalam Patua is titled ‘From the Interstices of the

City II’ and is mounted as a part of the collaborative efforts undertaken by

the India Art Fair ‘in supporting their endeavor to include contemporary voices

from the sphere of the Indian vernacular art practices’ (in the words of

O.P.Jain, director of Sanskriti Foundation).

(all works illustrated here by Kalam Patua)

Those who have visited the India Art Fair must not have

forgotten the exquisite display of the Kalighat paintings at the Delhi Art

Gallery pavilion and also the curiosity evoking arrangement of late 19th

century Company School art from the Swaraj Foundation. Ever since the Poddars

shifted their gear of their art collection from the contemporary to the folk

and traditional (thanks to the global interest in ethnic art as a part of

reconciling with the colonial atrocities and also as a part of co-optation of

the ethnical into the mainstream as an untapped source of creativity once

disparaged and now much valued for their intricate expressive qualities besides

the anthropological, ritualistic and sociological values) there have been

frantic efforts from other collectors and galleries to showcase and promote the

pre-modern and post-Mughal art as well as traditional and folk art from

different parts of India, qualified as the ‘contemporary vernacular’ or vice

versa. A new found interest in the Gond painters shown by both the new and old

galleries in the urban centers stands evidence to the fact that ethnical art

has not lost out to the contemporary expressions yet; perhaps that day is not

too far that the contemporary is displaced by the ethnic and vernacular.

When the India Art Fair takes interest in supporting the vernacular

art in India, this should be seen as a welcoming move and at the same we should

know that it is not just the philanthropic edge that is visible here but the

emerging market’s interest in co-opting all what is distinct and still

operative from without the mainstream economic structure built around art works

and their makers. Kalam Patua however has been around for quarter of a century

as an artist with considerable patronage from institutions as well as

individuals. Born in Murshidabad, West Bengal, Kalam Patua got his training in

painting ‘pat chitra’, scroll paintings as it was his family tradition and

gained considerable fan following and patronage from the rural folk and the

professional story tellers. His fame brought him an assignment from the French

Cultural Center, Alliance Francaise in 1990, to depict the history of French

Revolution in the Pata style.

In 1995, Kalam Patua came across the original Kalighat

paintings and spent considerable time in learning the techniques. Once he

gained the required finesse he chose to paint in Kalighat style that in pat

chitra style. But the dexterity of the Patuas, traditional scroll painters, to

adopt contemporary issues in their paintings helped Kalam Patua also to pick up

the contemporary issues in Kalighat style, which in fact had dealt with

contemporary issues of the mid-late 19th century in West Bengal in

general and Calcutta in particular. Initially Kalam Patua was an accomplished

copy artist of the traditional Kalighat paintings, which he happily did for his

clients. However, once he started working on the contemporary themes, the irony

and humor of the Kalighat paintings remained along with the style in him but he

almost pushed the old Kalighat painterly themes behind. But the spirit and the

referential depths of Kalighat kept coming back to his works as he reworked

many traditional themes typical to Kalighat paintings in the contemporary

context.

Kalighat paintings, thematically speaking were the

representations of the degeneration of the aristocracy and also the rise of the

greedy middle class. While the Bengali literature of the mid to late 19th

century dealt with the changes in the socio-political life a bit seriously,

often highlighting the tragedy of an impending collapse of the social structure

and also the aggression of the political resistance combined with the deliberate

attempts to erase class and caste by the educated class while keeping the

cultural standards high, the Kalighat painters were looking at the emerging

socio-political and economic scenario in more acerbically witty terms. “Kalighat

painting stemmed from the changing world of nineteenth-century Kolkata, where traditional

techniques of painting, iconographies, and art practices in general co-mingled

with Mughal court culture, Sanskrit Drama, the proscenium stage, and swiftly

churned out images from photo studios and lithographic presses in the fast

growing urban center, transforming folk art into popular genres”, observes

Jyotindra Jain in the catalogue.

The popularity of the Kalighat paintings could be rightly

attributed to the transformation that had been happening to most of the art

forms in the hands of the local artists who in fact became the meeting points

of the various styles floating in the society, as pointed out by Dr.Jain.

However at the same time, the thematic of these paintings also must be a reason

for their popularity for the content of these paintings always had suggestive

erotic connotations and were dripping mostly with scandal and gossip, which

were popular and prevalent in those days. Kalighat paintings seemed to have

shared a populist affinity with the elitist cartoons that used to appear not

only in the British press but also in the vernacular press. Illustration for

the literary works, posters for the theatre and also the racy narratives for

the emerging literate class also might have triggered the Kalighat painters to

make their works ‘vulgar’ (popular) and appealing to the mass.

In retrospective, in the case of Bazaar sort of art, which

Kalighat painting obviously was, elements of populism, which are often

connected to corporeal pleasures and thrills including clandestine affairs,

extra marital sex, lives of the entertaining women (courtesans), scandalous

affairs, murders and so on, were a pre-requisite. Hence the idea of refinement

for the subject matter was not the primary concern of the Kalighat artists,

which interestingly was not the case of the Pata painters who worked more on religious

mythologies with due seriousness and folk-ish playfulness or even later the

case was in their treatment of contemporary issues like the assassination of

political leaders, terrorists attacks and natural calamities. When Kalam Patua

paints his Kalighat style works, what we see is not the raunchiness of the

Kalighat painters on the contrary a refined sense of irony and humor without

losing the perspective of the subject matter that he is handling. This I believe

is because of his grounding in the pata chitra style and techniques.

There is a fundamental difference between Kalam Patua and

the other painters who work in the Kalighat style. Kalam Patua is serious in

his treatment without leaving the humor part aside. The humor is subtle and

intelligent. For example, when he paints the Birth of Postal Service in Germany

based on some literary source (as a tribute to his own life for thirty years as

a post master in rural Bengal), what we see is a master working, just like a

miniaturist in Mughal court with seriousness and complexities required to the

subject. The literary source is not followed to the dot but it is altered for

the pictorial purpose by compressing too many scenes into one and breaking the

linear perception generally required viewing a painting. The same sense of

seriousness and lightness could be seen in his India International Centre

series, which he had been commissioned by the trustees. Those who have visited

the IIC once, could really see how ‘realistic’ he is in his works and those who

have not seen the IIC also could enjoy exactly the way the Goan life is enjoyed

by people who have never been to Goa but have seen the visual renderings of

late Mario Miranda.

Kalam Patua is an artist who is innovative yet anchored in

tradition. He lets himself to travel to different subject matters but the

adherence with tradition that he observes in his works makes him attached to

the conventions of the Kalighat paintings and their themes. He paints a

contemporary domestic occurrence which has erotic undertones. Even if he has a

chance to break the conventions and remain within the style of Kalighat

paintings, Kalam Patua does not attempt to do so. Hence, such scenes still have

the traces of Radha-Krishna love games, the notorious Elokeshi-Mahant affair,

the arrogant Brahmin’s pretentions and the lecherous middle aged men. As I

mentioned before, Kalighat paintings while being the meeting point of several

styles and emerging social realities they also thrived on the degenerative tendencies

of the social life in Bengal, which was aspirational and self-defeating at the

same time. Perhaps, the contemporary Kalighat painting as practiced by Kalam

Patua also stems from the current degeneration of the contemporary society

perhaps selectively and intelligently seen by the artist himself. The market of

Kalighat paintings was initially limited to the vicinities of the Kalighat

temple in Kolkata but it moved from there to the houses of patrons. Now the

market has expanded and Kalam Patua has become a part of that extended market.

I wish he would also be treated one day as the way the Singh Sisters are

treated (as contemporary artists who use Persian and Mughal miniature styles).

No comments:

Post a Comment