(The new Ravi Varma book by the Piramal Art Foundation, Mumbai)

In Indian modern art history, Raja Ravi Varma stands more as

a problem than a solution. Today his works command very high prices and even

the most commercial of his artistic productions, the oleographs and the

products that came out in the market several decades after his death too have

become precious artifacts generating not only values for themselves but also

new avenues of art historical interpretations, anthropological enquiries and

aesthetic comparisons. Modern art history in India, often envisioned as a

linear stream of events with individual and collective milestones coming up

along the path, illuminated by erudition and darkened by deliberate obfuscation

of truths regarding art production and consumption, still finds it difficult to

accommodate Raja Ravi Varma as the pioneer of Indian modernism in art. In the

art historical narratives produced even today play the dilemma safely by saying

that Ravi Varma was a pioneer in employing western naturalism in Indian ethos

but not really the father of Indian modernism. By pushing both Ravi Varma and

his detractors of Bengal School in early 20th century into the

common category of ‘pre-modernism’, some historians have conveniently put the

cap (Mother of Indian Modern Art) on to Amrita Shergill without explaining

clearly how she was not using early 20th century western modernism

in Indian ethos. The only safe route for this people is that western naturalism

unfortunately is not equated with western modernism. So by virtue of style and

technique Ravi Varma remains technically pre-modern than theoretically and

practically modern.

A condemned Ravi Varma is as problematic as a lauded Ravi

Varma. Without dealing with a ‘mythical’ Ravi Varma, the real Ravi Varma cannot

be logically located within the modern art history. There are several texts

both in Malayalam and English that talk about Ravi Varma as a painter, a

visionary and above all a human being. Interestingly, except for a few foreign

researchers, most of the Indian chroniclers and historiographers, despite their

depth of research and erudition, have sprinkled a fair amount of suppositions

and attributions on to the biography of Ravi Varma so that today he stands like

an enigma for a contemporary scholar. When a contemporary scholar tries to crack

the Ravi Varma myth, he/she too, quite ironically tends to generate his/her ‘imaginaries’

about Ravi Varma. To see him and his works based on his own milieu of the

second half of the 19th century and emerging nationalist ideas and

ideals of that time, one has to have tremendous amount of detachment both from

the critique of Ravi Varma by the Bengal School and also from the historians

who have applauded him for being the first ‘popular’ painter in India. Ravi

Varma was not only popular but also populist. He had all the intentions to make

his works popular.

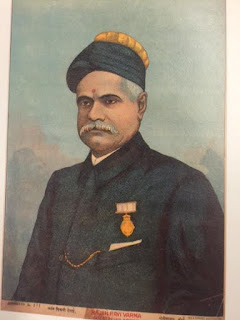

(an oleograph portrait of Ravi Varma)

A new book about Raja Ravi Varma becomes all the more

important and interesting because it is always curious to know what the contemporary

scholars are thinking about the master artist. Piramal Art Foundation has

brought out an interesting collection of essays and images in a book titled

‘Pages of a Mind- Raja Ravi Varma- Life and Expressions’. This books has come

out as a catalogue (though it is more than a catalogue) during the exhibition

early this year with the same name that has featured original paintings by Ravi

Varma, his brother C.Raja Raja Varma, photographic prints based on Ravi Varma’s

works, oleographs, embellished oleographs, advertising materials that used Ravi

Varma imageries and the painted porcelains statuettes made out of the artist’s

images. The temporality of the exhibition however is overcome by this book

edited by Vaishnavi Ramanathan of the Piramal Foundation. The book has six

interesting essays namely, Raja Ravi Varma: Life and Expressions by Farah

Siddiqui, The Painters, The Printer and a Diary by Dr.Erwin Neumayer and

Dr.Christine Schelberger, Ravi Varma and his Patrons by Vaishnavi Ramanathan,

From Maharajas to the Masses: Ravi Varma, the Maker of Multiples by Lina

Vincent Sunish, Idealizing the Real, Realizing the Ideal : Jewellery in the

Paintings of Raja Ravi Varma by Dr.Usha R.Balakrishnan and Culturing Indian

Cinema and Interdisciplinary Advents by H.A.Anil Kumar. The book also has an

‘image’ section where all the exhibits are presented with verifiable

provenance.

Before I delve more into the nuances of the essays, I should

say that many of the images presented in the book are not afore seen (at least I

have not seen them before) and each time my eyes hovered over them, I start

thinking about the kind of silent role reversal that Ravi Varma had brought

into his profession of making royal and secular portraits, besides making large

scale paintings based on mythological subjects, commissioned by the kings and

rich patrons. Ravi Varma did not paint ordinary women; he painted the likeness

of the women of the patron’s family. Otherwise Ravi Varma painted goddesses.

(He also painted men and gods but that’s a different point). The role reversal

happened in the case of portraying women as well as female characters. He made

sacred into profane and profane into sacred without much public hue and cry. Royal

women were ‘sacred’ members of the family and were not supposed to be seen

outside. But their portraits, though made for familial registration only, would

come out of the palace premises and would be subjected to the public gaze,

exactly the way the profane women are looked at. Almost at the same time, Ravi

Varma created goddesses out of the ‘profane’ women (professional models) who

went into the palaces and drawing rooms, assuming the quality of sacred,

respectable and adorable women (of the palaces). There are no conclusive

evidences to substantiate my views and I am not sure whether Ravi Varma himself

was aware of this role reversal done by him. Whether he knew it or not, it

remains as a (art) historical irony.

(a portrait by Raja Ravi Varma)

However, while reading an essay written by Vaishnavi

Ramanathan, I came across her quoting G.Arunima from her text where she said,

“G.Arunima writing on the portraiture in Ravi Varma’s works speaks of the

erasure of the notion of portraiture as a form that confers a specific

identity, since in Ravi Varma’s portraits there is minimal suggestion of

personality.” Ramanathan goes on to say

the following: “However it can be argued that by erasing the specificity of the

sitter, he opened up the image, offering a space for the viewer to locate

himself/herself. (……) In other cases, it was the space of the sitter where the

viewer could aspire towards the status and virtues that the sitter symbolized.”

(I seriously doubt any sitter would aspire to be a part of the portrait or the

portrait itself. This is a forced reading, I should say). Ramanathan’s whole

point is to say this: “Ravi Varma painted for people.” What happens here is

that Ramanathan repeats and unqualified statement of G.Arunima and goes by the

thread of that argument. Anybody who likes to look at a portrait painting,

he/she would definitely appreciate the ‘personality’ of the ‘sitter’ created by

Ravi Varma. His portraits are not open ended as the writer says. They are

definite and conclusive personality portraits that emphasis the ‘difference’ of

the sitter from the viewer.

The distance created between the subjects that Ravi Varma

chose to paint and the people who lapped it up including both the royal patrons

and later the masses who bought his oleographs is one pivotal point that many

historians have overlooked. This distance, gap, even we could say the rupture,

is what makes Ravi Varma’s paintings more enigmatic and alluring. When he

exhibited ten works commissioned by the Baroda King in Mumbai and Madras people

queued up to see the works and those were the talk of the town. (Had it been

the selfie days we would have had innumerable visual registrations for the

events). In the west it is called block buster exhibitions. Such exhibitions

are the dynamics of a particular historical time and developed out of

personality cult. People queue up to see blockbuster exhibitions (or they make

them blockbusters by queuing up patiently) because they are in awe of the

artist and the works of art. It is not the inter-changeability that the viewers

see with the works of art. I have never heard a visitor in the Louvre Museum

telling that he wished to be the sitter for Mona Lisa! Ravi Varma maintained

the mystique of being a painter that too a very popular one. The more popular

you are, the more your personal details are in the public domain, your physical

absence always makes you mystical and Ravi Varma knew how it should have been

maintained.

(an oleograph based on Ravi Varma's painting)

There are two things that demystify Ravi Varma; the

photographic reference visuals that Ravi Varma used for creating his secular as

well as divine paintings and the diary entries of his younger brother, manager,

studio assistant and fellow painter, Raja Raja Varma. Though these evidences

have been out there for public scrutiny for long thanks to our special interest

in protecting the Ravi Varma myths, these are not often addressed. Thankfully,

this book has an essay titled ‘The Printer and a Diary’ by Dr.Erwin Neumayer

and Dr.Christine Schelberger, which has all the details to demystify Ravi Varma.

The photographic evidences that they give from their book do not make us

condescend Ravi Varma but to appreciate him as someone who knew the world had

moved fast and decided to move along with it. He arranged models and

photographers in his studio and took the desired pose of the model from all the

angles so that he could make any alterations if needed. The advent of mirror

and lens was the prime reason for the development of perspective and

illusionism in western paintings. The arrival of camera and printable images

changed the very way of making paintings. However, photography was not seen as

a creative medium; it was treated as a mechanical mode of registration and

taking a photographic reference for making a painting was looked down upon as

the lack of skill or genius of the artist. This must be one reason why Ravi

Varma kept his photographic references as a highly guarded secret. The dairy

entries by his brother register the artist’s frustrations as well as

calculations, bringing the artist from his ‘divine’ position to a clever creative

person who knew the value of his ‘product’.

I have found a small discrepancy in the book as the

contradictory historical information clashes with each other in two different

essays. Vaishnavi Ramanathan says that we should see the ‘Raja’ in ‘Ravi Varma

alongside his thematic preferences.’ According to the writer, “By

reinterpreting divinity, imaging them as flesh and blood entities, doubly for

his own artistic desire and on behalf of his patrons one may say that Ravi

Varma was in a way reaffirming the divine status of himself and his royal

patrons.” We all are trained to call Ravi Varma with a prefix Raja only because

he too was born in a royal household. It has been taken for granted. However,

in the first essay written by Farah Siddiqui titled ‘Raja Ravi Varma- Life and

Expressions’, she digs out a different historical evidence. She writes: “In

1904, the Viceroy, on behalf of the King Emperor bestowed upon Raja Ravi Varma

the Kaiser –I –Hind Gold Medal. At this time Varma’s name was mentioned as

“Raja Ravi Varma” for the first time, raising objections from Maharajah Moolam

Thirunal of Travancore. Thereafter, he was always referred to as ‘Raja Ravi

Varma’. The artist passed away in 1906. He hardly lived for two years after

getting the status ‘Raja’. If that is the truth how Ramanathan’s suggestion

regarding the reiteration of the divinity of Ravi Varma by the prefix ‘Raja’

would become an acceptable fact, as the statement almost suggests that the

prefix ‘Raja’ was always there?

(a painted porcelain inspired by Damayanti by Ravi Varma)

The essay by Dr.Usha R Balakrishnan sheds a lot of light on

Ravi Varma’s study on the ornaments that he discerningly painted on various

subjects depending on their secular and mythical relevance. H.A.Anil Kumar’s

article on Ravi Varma’s impact on Indian cinema is a densely packed essay of

observations and suggestions. Lina Vincent Sunish, in her article ‘Maker of

Multiples’ traces the history of Ravi Varma as an entrepreneur who produced

millions of oleographs. Though a good amount of research has gone into it, her

thorough adherence to a conventional research essay style repulses the reader a

bit. The aspect that she could have developed the point, ‘the defining point of

19th century Indian renaissance is Hindu civilization’ as stated by

Geeta Kapur further in order to take the stress from ‘Hindu Civilization’ to

‘Hindu Nationalism’. The attempts that Lina makes peters out as she takes the

research line of Patricia Oberoi, Kajri Jain and Sucharita Sarkar. If it was an

attempt to define the growing nationalistic tendencies in today’s

socio-cultural and political scenario in India and its comparison with the then

emergent (Hindu) nationalistic milieu and Ravi Varma’s non-commitment to both,

the essay would have been much more interesting.

(an advertisement inspired by Ravi Varma- All images are from the book. Poor image quality regretted)

I grew up in a village where most of the Hindu houses had

the Ravi Varma oleographs. In my grandmother’s home there was a big oleograph

that showed the image of a baby Krishna stealing butter from a pot. I used to

get into this small household temple that smelled camphor, incense sticks,

flowers, sacred ash and sandal paste whenever I could escape the watchful eyes

of the elders and used to keep on looking at this bubbly baby boy with shiny

large eyes, curly hairs and a peacock feather fitted above the forehead. That

baby boy looked more like a cherub than a boy like me. I used to wonder why the

gods were not looking like the people around me. As I grew up, I understood

that Ravi Varma also had a colonial view on nobility and sophistication. It was

his birth, upbringing and training. He subverted this colonial view indirectly

by transforming ‘public’ women into private goddesses. However, in his pan

Indian imagination as we see in the galaxy of women, he did not paint a woman

who looked like a typical woman who worked in his home or in the fields. Ravi

Varma had made exclusions; histories written about him also have made

exclusions. We do come across court painters like Alagiri Naidu and Ramaswamy

Naickar as Ravi Varma’s contemporaries. They were court painters. But we do not

see any other individual painters from outside the court. Blame it on

patronage. But immediately after Ravi Varma’s death, we see in Travancore, so

many individual artists painting in Ravi Varma style, most of them trained by

Ravi Varma’s son and his disciples. Till a couple of decades back we could come

across Ravi Varma school painters in Trivandrum. However, most of them are

excluded from art history. I strongly believe that Ravi Varma’s history will

become scientific history only when the histories of his contemporaries and

successors are also included in the narratives. Otherwise we will have to

depend on a lot of legends and myths, just to satisfy our own lack of interest.

This book is a worth reading one and definitely a collectible.

No comments:

Post a Comment