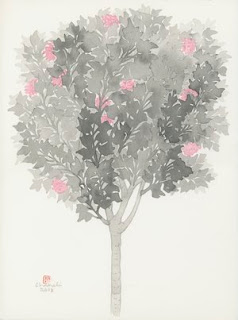

(Painting by Bose Krishnamachari)

No question is ever asked if there is no answer to it. So is

true to say that each answer also carries a question in/with it. That means

questions and answers are never two different entities but the extensions of

the same in all the possible directions. In an inextricable relationship they

are entwined forever, at times manifesting as questions and at other times

coming forth as answers. Any question left unanswered would wander like ghosts

making lives of the people around it difficult. Answers that go without

questions too are like ghosts, but of a benign variety like a truism destined

to remain in the text books without ever getting underlined or quoted. So it is

always good to answer a question and question an answer. Proving my motto

right, my student, aspiring critic and also a future art entrepreneur who would

like to start an ‘intelligent gallery with definite commercial intent’, Oorja

Garg has forwarded this question which came up in her mind after reading my

article on abstract art as an answer to her question regarding the topic. I had

concluded my previous essay with a statement that ‘along with several genuine

abstract artists you will always have some imposters.’ Now Oorja would like to

know how as young art critics (future art critics) they could distinguish a

genuine abstract artist from an imposter.

The question has an answer; perhaps several answers.

However, I would like to stick to the genuine and imposter binary in order to

arrive at some feasible answers. The first and foremost answer is that of the

‘disinterested’ analysis of a work of art by the art critic, taking its

formalistic and thematic ingenuities and then moving from there to the

contextual veracity of the same using the objective critical parameters set up

by the critical and historical discourses pertaining to it. That means, a

critic should be primarily a ‘disinterested’ personality. The term

‘disinterestedness’ in the critical parlance is a late 19th century

British formulation by the literary critic Mathew Arnold, which had been taken

further by the pioneering modernist, T.S.Eliot. Disinterestedness is a

non-partisan attitude that highlights pure objectivity. When disinterestedness

is the key to the analysis of a work of art, what a critic primarily does is

looking for its ‘originality’, it’s sort of non-indebtedness to the immediate.

Both Arnold and Eliot speak up for ‘Tradition’ and its role in framing the

individual talents but their emphasis is on the transcendence of the past to

the present and its ability to move towards future. This locates a work of art

as the product of a historical process that the registration of the immediate

contemporary events. Disinterestedness is possible when the critic approaches a

work of art using historical parameters to which he/she does not have any

partisan relationship. According to them pure objectivity is possible in

discerning the genuine from the fake/imposters. Also the emphasis is on the

application of objectivity, which does not have anything to do with artist’s

personality or surroundings, therefore it could always move around formal

values and experimentations. The early 20th century abstract art was

all about these objective experimentations, which almost appeared as an

aesthetical issue rather than any socio-political or personal-cultural issue.

(Painting by Velu Viswanthan)

(Painting by Velu Viswanthan)

Formalism has its own traps and it did/does appear

throughout the 20th century and even now it happens in the making of

the abstract art where the imposters could smuggle their wares in as genuine

products. Formalism stresses on the surface values while balancing it with some

internal meanings, which need not necessarily be the starting point for the

onlooker or for the critic. That means, if an artist has come up with a new

texture, a new treatment of the pictorial surface, a new impression, a new

adoption, a new juxtaposition, a new visual value and so on in his pictorial

plane we do not have any devices to discern whether it is genuine or posturing.

While formalism and disinterested approach of the critique collapse the

boundaries of sense and make the genuine appear as a posturing and the

posturing as genuine. This is the reason why so many artists who have been

either lacking in skill, craft and concept or clever enough to pass of all

those lacks as ingenuity present their abstract works and gain a sort of market

success and acceptance in the general art scene. As I had explained in my

previous article on the theme of abstract art, the experimental aspect of art,

especially that of the abstract art was taken as the prime quality of ‘modern

art’. So anybody who would like to jump into the bandwagon of ‘modern art’ could

come up with some color blotches and patches and say that they were modern

abstract art works/artists. It is difficult to argue with such artists because

they would hold onto the features of formalist modernism and say that they have

all those in their works. Besides, the universal modernism functions properly

when it does not fix its expression in geographically or culturally or

linguistically defined forms or figures. Formal abstract experiments which

could be easily abstract expressionism also overcome those abovementioned

specific definitions. In this false universalism, the imposters thrived and

they still do.

(Painting by P.Gopinath)

(Painting by P.Gopinath)

This brings us to a point where we are forced to rework on

the objectivity of disinterested criticism. While keeping the historical

experience of it and the employment of such parameters intact, we could also

add the critic’s subjectivity in the whole discourse and discernment.

Subjectivity taking an upper hand in the critical discourse may be fallacious

because of the possibilities of personal preferences and bias. Therefore we

need to redefine the nature subjectivity when it comes to art criticism or any

kind of criticism; subjectivity has to have objective nature that means one

shouldn’t be too biased to see the posturing. Secondly, subjectivity cannot be

over emotional or sentimental; but it should be informed and has a deep sense

of not only art history but also the social history within which art history as

a genre is always operated. Also the subjectivity of the critic should be

interdisciplinary in which he/she should be taking the socio-cultural,

politico-anthropological, linguistic-economic factors of the artist and the art

work (abstract or figurative) into consideration. This also leads to contextual

criticism where the general norms of a society at a particular time in which

such works of art are produced come to play a big role. That means, the

critic’s subjectivity should be formed out of all these in order to gain

sufficient objectivity in discerning the good-bad, genuine-fake identities of

the (abstract) art.

(Painting by VS Gaitonde)

(Painting by VS Gaitonde)

The mere posturing of the artists who say that they are at

par with the masters of the international abstract art (they are international abstract

art because they are discussed in the mainstream art discourse including the

economic discourse) only because their formal values are not different the

established ones. It is where the critic’s informed subjectivity should

intervene. If it is all about formalism, then there could be a comparison

between the formalism of the genuine one and a posturing. While the genuine

ones give out a sense of harmony, rhythm, balance and all that settle the mind

of the onlooker and send him or her to a kind of contemplation not necessarily

about the work of art in question but about anything related to that, and bring

in a sort of deep silence, then we can say that the formalism is successful.

This argument could be contested by showing Marc Rothko on the one side and

Jackson Pollock on the other. While Rothko’s paintings give this deep

meditative feel, Pollock’s may send the viewer to some sort of chaotic dance.

Here the critic could employ his/her interdisciplinary approach and understand

why Pollock was doing like this and Rothko was doing like that. In short, what

I say is that the critic should employ the subjective understanding to discern

a fake from the genuine. Faking a contemplative depth is what most of the

imposters do for creating their abstract art. They do not look for the

intrinsic values that I have explained above but try for the production of a

formal look. And their only escape route is that no abstract could be copied as

it is because very subjective formalisms cannot be copied in its lawless randomness

or carefully calculated texturing.

Most of the times, abstract artists are made famous not

because their works have intrinsic qualities but they are clubbed into a sort

of contemporary tradition. We have several masters who have done good abstract

works. At the same time once their time is up we come to see his or her

disciples coming up as the next generation abstract artists with some

variations in existing formalism of the master and getting established by

virtue of being the students of the departed master or just by mere

association. There are abstract artists who rule the market only because

certain school has produced them. The market and its players produce the value

by creating narratives around them and their schools, and bring them to the

auction market and fetch huge amounts of money. This in turn gives an impetus

to many more so called ‘modern artists’ to come up with abstract art. Often the

abstract art is projected in the market thanks to extrinsic reasons that do not

have anything to do with aesthetics that these artists intend to produce. We

cannot wish away this abstract lobby and also the coterie that supports it.

Hence, the onus of identifying a genuine abstract work of art falls on to the

shoulders of the critic him/herself with those subjective and objective tools

that I have mentioned at the outset of this article.