A self-portrait, as far as an artist is concerned, is a very

special and significant moment for he/she does not come to model for him/herself

that often. That means self-portraiture is a moment of arrival and a moment

before departure. Mostly done in a single sitting, a self-portrait heralds the

arrival of the artist to that moment which finds himself too inspiring to

avoid. And he would hanker around for long as the moment of arrival engenders

the moment of departure as well. Hence, we could say self-portraits are a

spontaneous yet very volatile moment that anticipates an ‘exist’ rather than a virtual

sojourn within the space and time. It is different from a photographic

self-portrait because in photography the portrait happens in a moment though

after much deliberations that would result into the desired (self) portrait but

in the case of painted self-portrait the result spreads through many moments

which could be a single sitting or an extended one segmented into various times

of the day or over a few days.

An artist, while doing a self-portrait examines himself,

exposes his inner thoughts, turbulences and vanity he also inadvertently lets

the people to come and take a good look at his ‘original self’ which remains

hidden on a normal day at any given point of time. Before the easel where he

does the act of self-portraiture he is also in an interim space, not exactly

between the entry and exist points as mentioned before, from where he looks at

his reflection on a mirror and at the canvas or surface where he makes the

portrait. In this sense, an artist is an observer and the observed, the subject

and the object, the object of his own desire and the very image of it. He may

be flaunting his artistic prowess to create a likeable self-portrait in terms

of likeness and an impressive one, in terms of its execution. He stands to gain

accolades but at the same time he is at the edge of a cliff where he could lose

the grip on his ego and fall into a ditch of self-exposure. A posturing could

betray the underlying fear and trepidation and even if he denies his weaknesses

the apparent strength itself could collapse in the weight of the denial. In

short self-portraiture is a dangerous game, and adventurous pursuit, creation

of a brittle auto-fiction, if not a plain confession.

(Shibu Natesan Self-Portrait Number 2)

In this short essay an attempt is made to locate the six

self-portraits by the noted artist, Shibu Natesan (b.1966), done during the lockdown

days in March 2020 in Wales, England. He was in London, spending time with his family

when the Covid-19 pandemic broke out in the world. Wales, a country side

location where Natesan’s wife, Kate Bowes, an artist herself, has her ancestral

home, became a retreat for the artist and family as they found the place safe

from the virus attack. A retreat is a happy retreat when the move is willingly

done but when locked down from outside even the best place in the world could

exude a sense of jail. Any creative person overcomes such moments of locked up

feeling by engaging with it directly or by taking the attention away forcefully

from it. Natesan seems to have done both of these; in his profuse landscape

paintings one could see how the artist takes his energies away from the threat

of the virus by indulging deeply into the beauties of nature and painting it.

But when it comes to the direct engagement with the sense of the pandemic

lashing out all over the world, he could do nothing but looking at his own self

and paint it.

Natesan has been a master of self-portraiture. His mastery

has also been seen in making portraits of unknown and well known people, always

willing, patient and enthusiastic sitters for him, whom he meets while his

innumerable journeys to make plain air paintings of the landscapes. Perhaps, he

treats the given landscapes in front of him as people and models who prod him

to paint their likeness, most importantly, the way he wants. In the context of

the pandemic the models are always possible distractions and sensible

engagements than a dialogue with the situation. Misery cannot always be dipped into

beauty though misery has its own beauty when captured in forms and shapes, in

moving or frozen pictures. Misery of the human beings in any part of the world

has to be addressed and if they are within the means of addresser it should be

alleviated. But alas, an artist is just an individual who could flag out,

scream out and point out, but never offer solutions or means of it. In art

there are no immediate or long term solutions to problems. But there are

locations in art where one could see how the world should not repeat certain

follies.

(Desperate Man by Gustav Courbet)

Self-portraiture is a self-examination; the way a woman

searches her bosom to make sure that she does not have any carcinogenic lumps

there. It is tender yet apprehensive; it is curious but pregnant with the possibilities

of future miseries. It is self-assuring but doubt inducing. It is a private act

yet once doubts confirmed it is liable to be exposed and treated. That means

self-portraiture is a beautifully rough act; a violent yet pleasurable and

dangerous self-indulgence. Natesan takes this risk and the risk becomes too

palpable and visible when we see very few artists have done self-portrait in

contemporary Indian painting. Self-portrait as a part of the narrative or as a

surreptitious intervention by the artists who did miniatures and votive

paintings for the patrons is a different genre altogether though art

historically they too are treated as self-portraits. But Natesan’s is more

independent and less interventionist like those in the lineage of Rembrandt and

Courbet. In India, an artist like A.Ramachandran has dared to involve his

self-portrait in his narrative works but the prolific doyens like Ram Kinkar

Baij and K.G.Subramanyan have always resisted the impulse to make

self-portraits in or as their works of art. This gives a unique position to

Natesan in the art historical discourse in India.

Self-portrait number one shows Natesan sitting in an erect

posture, palms on his knees and giving a side glance with the lips held tight.

The summer in Wales is pleasant yet there is a nip in the air as the round neck

full sleeve sweater worn by the artist suggests. The background is plain. The

flowing locks are open and the light falls on his face from the right side of

the painting a la a Vermeer painting. As we know that the Covid 19 was around then,

the artist’s erectness shows his alertness to the situation. The tight lips

suggest that he is yet to make head or tale out of the pandemic condition. He

seems to be a bit tensed for the sudden shift to the Wales. The Grey tone of

his clothes though a bit mundane should reflect the undecided nature of his

mind for the time being.

(Shibu Natesan Self-Portrait Number 3)

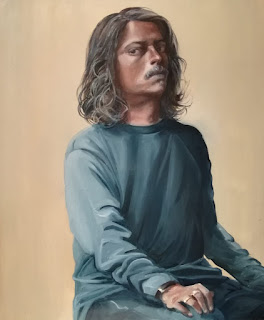

In the Self-portrait number two Natesan seems to have grown

familiar with the surroundings and has decided to put up a show for his own

enjoyment. The half cushioned hacked and apparently the same grey t-shirt seems

to make a good blending. What makes the portrait interesting is the red cap

whose reference should be to the reggae musicians like Peter Tosh. His gaze is

sharp and is directed at the imaginary viewer who is none other than himself.

The gaze is quite piercing as he tries to look into himself and the show that

he has put up for himself. The semi parted lips show a bit of ‘I do not care a

bit’ attitude often exuded by the Rastafarians. Still the facial muscles are

tensed and there is no chance of him relaxing internally. The work has certain

self-referential qualities as similar posture could be seen in some of his

early self-portraits.

The third Self-portrait seems to have originated from

Natesan’s mental dialogue with Gustav Courbet who had done the self-portrait as

a desperate young man. Courbet’s face is upfront and to the viewer. The eyes

are wide open in it and one could sense the pang of a wounded soldier in his

face. Natesan perhaps avoids the pain on face. But the expression betrays the

desperation that he feels inside. The light falls from the right on his back

highlighting the contour of the body as well as the folds of the clothes. He

refers back to the works of Jean Ingres, perhaps in this work. As the gaze is

averted and an extra sharpness given to the edge of the nose gives a sense of inquisitiveness

about the surrounding that has just beckoned him back. Perhaps Courbet and

Natesan have the same thin moustache!

(Shibu Natesan Self-Portrait Number 4)

The fourth self-portrait is more typical of Natesan where he

seems to have adjusted to the pandemic situation that has held him back in

Britain for more than expected. The gaze is direct and there is a sense of

reconciliation in his eyes. The same clothes as in the first portrait show that

he has been home bound for some time and his outing to do landscapes has not

really been regular. The scarf around his neck in the previous portrait seems

to have obscured deliberately to give a look of a lowered mask, which has

become a health protocol all over the world. Once again the gloomy grey has

come back as a background and the summer light hasn’t really lit up the mood or

room. The extended left had must be holding on to the frame of the canvas on

the easel but he leaves it obscure and lean as he thinks it is unnecessary to

think about the details and go for what is apparent.

(Shibu Natesan Self-Portrait Number 5)

It is quite Zizekian as we come to the fifth Self-portrait

of Natesan. He has all braced up to face the world. Covid or no Covid, I am

here to work, he seems to declare the world. Zizek says that when we are

afflicted by an illness we go through five stages of dealing with it, namely

Denial (No it cannot happen to me), Anger (What on earth it came to me, why didn’t

it spare me), Bargaining (Oh good Lord, give me some time so that I could

finish my duties and tasks), Depression (No way…I am down now..), and

Acceptance (Come what may let me live the rest of my life happily and I ready

to die). Natesan in this painting seems to have reached the final and fifth

stage; acceptance. The red sweater and apron shows the sanguine nature of the

determination. Like Ernst Ludwig Kritchner, Natesan holds an erect brush in his

right hand to assert his decision to live and paint. A portion of the adaptable

easel is seen reminding the convention of Velazquez or Van Eyke. The mandatory

mask is around his neck and what makes the painting assertive is the background

where the flat emptiness is replaced with a traditional wooden shelf where

crockeries are beautifully arranged. The gaze is more direct and cheerful. The apprehensive

holding of lips is gone and they are shown full below the greying moustache.

(Shibu Natesan Self-Portrait Number 6)

Once all five stages are over and the summer has made the surrounding

more beautiful than ever and the hope is fully back in the minds of the people

as well as in the artist, the self-portrait number six shows an absolutely

different feel. Natesan is seen more like a contemporary troubadour, with a

Neruda like hat and a high neck Indian half jacket. A middle dandy with flowing

hairs has his chin up and a quizzical look in his eyes. Like the second

portrait here too you could see an act, a posture but with more lightness than

the former one. Though the eyebrows are crooked to show questioning look, it is

not really a serious one but a moment before the exit, a laughter perhaps.

Natesan has also done a series of oil and watercolour landscapes immediately after

March 2020. Rembrandt was examining himself through is self-portraits while

registering his ageing but in Natesan’s case it is not the registration of

ageing but the time that has held one and all in thrall without letting know

anyone about their lives or deaths. One could see how the emotions festered in

each person in the world which must have taken different forms of expression

including poetry, painting, music, pornography, self-portrait, short film

making and domestic violence. Natesan’s self-portraits are not his picture

alone but the picture of all the people who have lived in March 2020 and lived

beyond it.

-

JohnyML