(Artist Pravin Dhanuskar)

“Art is not a mirror held up to reality but

a hammer with which to shape it,” said the famous German playwright and poet,

Bertolt Brecht. The re-articulation of the classical dictum, ‘art is a mirror

held up to nature’ came via William Shakespeare had taken an absolutely

different form, shape, complex and effect in the hands of Brecht. For him art

is a hammer that could ‘deconstruct’ and ‘reconstruct’ the society. It connotes

the physical power directly employed unlike in the technological world where

physical power is always mediated through machines, tools, networks and

retailing. Here in the case of Brecht we should be taking ‘physical power’ as

the imaginative power of the human creator who mediates it through his/her

works of art. Pravin Dhanuskar is quite Brechtian in this sense both in

revealing the epic theatricality of life and also in eking out a response from

the audience.

Epic theatre, though the word connotes

magnificent scale and form, does not really reflect upon classically epical

subjects but the topics and subjects around the artist and builds its dynamics

in the course of an interactive display of histrionics. We see the same in the

works of Dhanuskar as the subject matter that he chooses for painting those

‘dramatic’ scenes is rightly picked up from the society around him. Hailing

from a farmer’s family and later on migrated to a buzzing metro city like

Mumbai Dhanuskar knows the best of the former and worst of both the worlds. But

that does not put him off, nor does he turn into an existentialist who either

turns his gaze into oneself or unto his shadow. Instead, Dhanuskar boldly looks

around and picks and chooses such vignettes of events that could be easily

identified by even an unsuspecting spectator in an art gallery. The images that

I would be elucidating soon in the following part of this essay have a telltale

nature and invite the viewers for a closer inspection. The format that

Dhanuskar prefers may not be epic in scale but the essential politicization

involved in the image making process has an epic quality.

Dhanuskar’s politics is his art and vice

versa. Outside the art the politics of his kind cannot function for the sheer

functional impossibility. An artist who speaks of the deprivations that the

farmers face today in India may be ostracized just for his dissenting voice.

While he is expected to be singing praises of the sacrifices done by the

farmers and soldiers for the country, his dissenting could be taken for an act

of betrayal and his dissenting voice might place him among the

anti-nationalists. In such a scenario, telling truth and using the hammer at

once to wake up the society and reconstruct it needs a different aesthetical

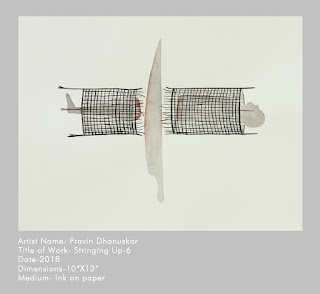

strategy. Dhanuskar employs the image of a cage (as quotidian as the wire mesh

cages that protect the saplings along the road dividers and footpaths) and

attributes a different functional value to it. He makes a series of ink drawings

titled ‘Stringing Up’ in which instead of the expected saplings he places an

emblematic human figure, which is attacked and vandalized by daggers of

different sizes from all the sides. At one point a stringed cage is cut up into

two in the middle and the process the man inside also is cut into two parts.

A sapling is expected to be nurtured and

cared for. That’s what a farmer does to a sapling or the paddy shoots in a

field. The wire mesh cages on the road sides are supposed to protect the

saplings that would grow into trees to give shade and oxygen to the future

generations. Gardeners water them from all sides and even make the soil at

their roots loose so that easy absorption of water is made possible. But what

happens here is the ruthless attack. The sapling is replaced with the

emblematic farmer himself and he is ‘cabined, caged and cribbed’, besides he is

vandalized and annihilated. Dhanuskar’s politics comes in such a metaphorical way,

which is akin to the epic theatre that Brecht had initiated in the last century

Germany. The simple, harmless and a bit childlike ink drawings in the first

instance itself cajole the viewers to what they know; it is then they are

forced to see how do they know it and why do they know it. The moment they

understand it through the process of general information regarding the

contemporary times of our country, one enters into the world of such simple yet

difficult metaphors and feels the persuasive politics of those images.

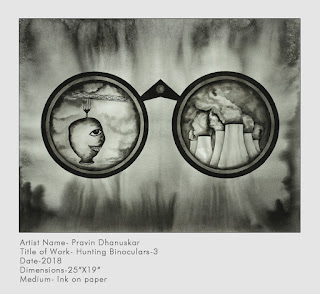

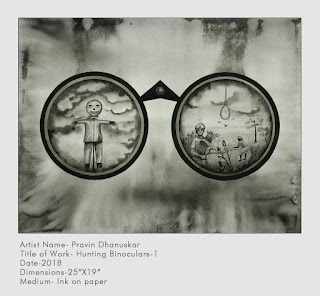

‘Hunting Binoculars’ is an interesting series

that is treated a bit more directly than the other works by Dhanuskar.

Binoculars, as we know, do not hunt; they are used by hunters. Binoculars, at

the same time suggest the safe distance that the hunter/s takes during the act

of hunting. That means from a safe distance a group of people are hunting

hapless human beings who live harmoniously with the nature. However, the moment

the hunters locate a place for their game the fate of the dwellers in those

places is changed forever. They get displaced or become permanent migrants

elsewhere. Some may become urban poor and some become urban laborers. It is the

grand metamorphosis that India today is undergoing; transformation of people

from human beings to subhuman creatures in a world of urban slavery in a Kafkaesque

turn of events.

In one of the lenses we see an emblematic

face; it could be that of the hunter or that of the viewer. Here is an

interesting alchemy as we look through the lens of a pair of binoculars we too

become a part of the hunting group temporarily and the sight seen through it

must be fascinating. In the other lens there appear three scenes; one, the face

of a troubled farmer and the field sprawling behind him, two, a jumble of

worshipping centers like temples, mosques and churches, and three, a cluster of

nuclear reactors. Dhanuskar quite subtly identifies and sets before us the

conflict zones without making much hue and cry about it. We could see

development, unrest in the agricultural field and religion are the three

conflicting points in our society. People are ready to die and kill for these

three things and it mars the whole onward journey of a might country like

India. Perhaps, our politicians want to retain these issues unaltered or they

do not want to find a permanent solution so that the vote bank politics would

find its future niches decelerating the progress considerably. What one never

fails to notice in Dhanuskar’s ‘Hunting Binoculars’ series are the faces of the

emblematic human beings that almost become the faces of Scarecrows.

‘Scarecrow’ is a closer to home metaphor

for Dhanuskar as it stands curiously and eerily for the others (and absolutely

naturally for the farmers in the fields or living in the farming villages) and

with its hidden power scares away the avian pilferers. Here, Dhanuskar gives a

twist to the meaning of a normal scarecrow; the hidden and unarticulated power

of a common man, as it was a reflection of the Bollywood line, ‘Don’t

underestimate the power of a common man.’ At the same time scarecrows could be

simple effigies that represent evil powers and negativity. In Dhanuskar, the

scarecrow faces oscillate between these two meanings. In his series, ‘Height of

Memorial’ he almost lampoons the political bigwigs who go around in a statue

installation spree. A statue of any height, made of any material or has any

ideology to back up is bound to collapse in the long run or rather assume a new

meaning in a changed time. Dhanuskar forwards this critique on memorials

through this series where the faces of the statues, as expected become the

faces of scarecrows. The same political satire once again comes to play in yet

another series by Dhanuskar, titled ‘Trepidation.’ The same scarecrow faces are

repeated here also but they are fitted on to the bodies that enact the famous

yogic postures and challenges, advertised and propagated by the powerful

mainstream media and the power centers itself. The viewers need not go very far

to understand what the artist exactly wants to convey. But he forwards the

critique with discretion and does not want to hurt anybody’s sentiments

unnecessarily. As a master craftsman, Dhanuskar knows how to hammer the society

and wake it up.

‘Pachyderm-ic Pressure’ is another series

that Dhanuskar brings out in this exhibition without losing his critical verve

but keeping the idea of epic theatre in mind. Elephants are curious animals,

reminding always of the magnificent forest lives of yesteryears and the distant

historical times when the mammoths and dinosaurs had ruled the earth. However,

in his series Dhanuskar presents the elephants as multi-trunked magical

creatures that could exert their pressure on the society and tame it; an

elephant that grows to the level of a monarch or an autocrat by virtue of his

mightiness could control societies with fully developed and intelligent human

beings, and render them absolute puppets in his hands. Whether this series

should be taken as a direct commentary on social events or they should be seen

within the aesthetical context is up to the viewers, and that is the beauty of

the epic theatre unlike the proscenium theatre based cathartic presentations. In

this context, a latest series titled ‘Ill Omen’ depicting three nocturnal

creatures should be mentioned. This work, which is quite striking, comes as an

underlining to his politico-aesthetical thoughts. Dhanuskar believes that the

bad times are not over; it has just begun and many more to come. How and when

it would come, as an artist he does not have answers, but he sketches out the

ominous times where we are destined to live through.

I would conclude this essay by mentioning

two video installations that Dhanuskar has presented in this exhibition. One is

titled ‘Orthodoxism’ and the other is ‘Vibration of Negativity’. The titles as

well as the presentations are simple and direct but as I mentioned in the

beginning, there is an epic theatre quality to these video installations.

Orthodoxism, as the word suggests, has political orthodoxy working overtime to

retain their chairs of power. They are ready to do anything for that; including

bribery and backstabbing, kidnap and murder, confinement and encounter etc. In

the video we see masked characters in a mime charade enacting telltale acts of

power struggle but what makes us sit up is the sound track that contains the

screeching and howling of these ominous characters. All of a sudden we realize

that our lives are enveloped by such inhuman cacophony that often we get

accustomed to. Separated out of the living context and posited in the

theatrical situation, this shrieking wakes us up, hammers us down and instills

fear in us but at the same time the courage to call out ‘stop’. In ‘Vibration

of Negativity’, Dhanuskar goes back to his familiar zone of agricultural field

where he places the scarecrow as the central figure. We see a man trying to

approach it but failing in each attempt. There is something negative about it

the scarecrow; taken in a positive sense the negativity scares off the birds

but in a critical sense, as we see here, the scarecrow becomes a stand in image

for the autocrat who does not allow people to go near him. He is not only

negative but also dispels any efforts to assail it. It takes a lot of effort to

cross the invisible ring of negativity that it exudes and overthrow it.

Pravin Dhanuskar is an artist who takes

subtlety as his mode of action; but his mode of expression is different.

Through very subtle washes and strokes he creates such images that surpass

their shyness and take people by force and ask them to delve deeper. Playing

with the familiar today in our socio-political scenario is as good as playing

with fire. But one needs to develop special techniques to avoid headlong

collisions with the current times but with well-aestheticized moves he could

take it into his stride and articulate for an enlightened and politically

conscious audience. Pravin Dhanuskar has this wonderful ability/agility to

handle the current socio-political forces and it gives him the courage to be a

true political artist in one of the pivotal phases of 21st century

India’s history.

No comments:

Post a Comment